Britain’s Hidden Role in the Armenian Genocide

By T.J. Coles

13 May, 2015.

Armenian Children.

The Armenian Genocide is commemorated this year. Britain’s role is not a secret, but has remained hidden because scholars have not connected the dots. Building up the Turkish war and technology machine, siding with Turkey’s rival Russia in the First World War, and refusing to intervene directly, made Britain a major enabler of the genocide.

TELEGRAPHS

Britain and Russia vied for influence over central Asia and the Middle East. During this period, Britain invested in Turkish bonds, railways, telegraphy, and munitions. Historian Yakup Bektas notes that in Ottoman Turkey, ‘the telegraph came to symbolize the sultan’s authority and geographic reach, a socially constructed symbolic linkage that was skillfully exploited by the British promoters who marketed it as an imperial design associated with the sultan’.1

The telegraph gave the Ottomans a kind of ‘information domination’ for the period and ‘kept their empire united’. Bektas goes on to note that the technology was heavily promoted by Britain for its own strategic interests. ‘The telegraph, like railways and other industrial enterprises, found an open door to the Ottoman Empire during the Crimean War (1853-56)’. For a time, Britain sided with Turkey in opposition to Russia.2

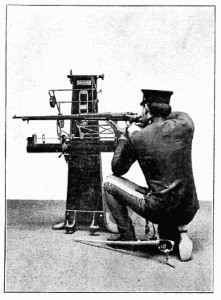

Telegraphy in Turkey.

Bektas also notes that telegraphy ‘became an even more powerful political tool during the long reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II (1876-1909)’. Bektas notes that many Armenians were given administration and hi-tech jobs on the telegraph system; a cruel irony given that it was used in their downfall. Bektas concludes that a leading Young Turk, Talat Pasha, who become the Interior Minister, ‘was formerly a mere telegraph clerk at Edirne and later at Salonika. The telegraph enabled him to organize and spread the movement in spite of the sultan’s spies’. Pasha was instrumental in the genocide.3

ARMS TRANSFERS

Referring to the biggest arms contract with Sultan Adbulhamid, ‘The foreign offices of the countries whose companies strove to procure the contract – Germany, Britain and the USA – were officially involved in the Ottoman war business’, writes historian Naci Yorulmaz. 4

As the Turks increasingly relied on German investments, Britain shifted its allegiance to its former enemy Russia. Gregory Topalian notes that during the Russo-Turkish War 1878, the Russians captured Turkish territory populated by Armenians, including Alshkert, Batum, Kars, and Sarikamish. One possible route to avoiding the genocide was to grant Armenia autonomy. Pursuing strategic, anti-Russian interests, ‘Britain was anxious to contain the Russian sphere of influence, and the subsequent Treaty of San Stefano was a major disappointment to the Armenians who still found themselves under Ottoman control’.5

British weapons pamphlet.

Britain promised some protection to Turks against Russian expansion, but, following the Treaty of Berlin, ‘the six vilayets were now no longer referred to as Armenia, and the Armenian situation there had become even more precarious’ (Topalian). The US priest, Reverend Geoffrey H. Hepworth, wrote at the time that, ‘England has assumed a sort of protectorate over the Armenians, but her protection is a sham and a shame. She can talk eloquently about oppression, and she can play the simple and easy game of bluff’.6

Hepworth’s bitter denunciation continued: ‘when deeds are to be done she [England] retires from the field. She is more responsible for the cold-blooded murders which have come near to exterminating the Armenians than all other nations put together’. Hepworth concludes that ‘She is bold with her lips but cowardly with her hands. If she and never known that there was such a people as the Armenians, I honestly believe the massacres would never have taken place’.7

British bikes for the Turkish military.

Britain was still sending state-of-the-art weaponry to Turkey. The Wilkinson Sword Sub-Target Rifle was described in a pamphlet from the time as ‘the instrument is capable of being used to great advantage with the disappearing target, as well as for snap shooting’. The pamphlet noted that the ‘Machines have also been received on behalf of H.I.M. The Sultan of Turkey’. A weapons history website notes that the Birmingham Small Arms Company placed ‘Orders for Rifles and Ammunition for the British, Russian, Turkish, Dutch and Portuguese Governments[, which] kept the Company fully occupied until 1880’, when it also supplied militarised bicycles.8

Until the Germans successfully competed for investments, Britain held 10% of Turkey’s bonds. 40% of Britain’s investments in Ottoman Turkey went to the railways. Bektas writes: ‘Railroads … enabled the rapid transfer of troops and material, which helped the central government suppress revolts and exercise control over distant provinces’.9

British and German train technology deporting Armenians to camps.

HUMANITARIAN INTERVENTION

By 1914, it was quite clear that Turkey had an extermination programme. Interior Minister Talaat Pasha—the former telegraph operator—explained that the Young Turks’ objective was to ‘destroy all the indicated persons living in Turkey … Their existence must be terminated … and no regard must be paid to either age or sex, or to any scruples of conscience’.10

British Member of Parliament, Aneurin Williams said at the time (to quote a general consensus): In Armenia ‘There is no security for property or for life. There is no security for the honour of the women of the subject populations … it is slow torture, varied by big massacres’—an intergenerational crime, he said. Williams notes the ‘massacres deliberately organised from Constantinople, and in which not only tens of thousands but some say one hundred—and some say two hundred—thousand people have perished’.11

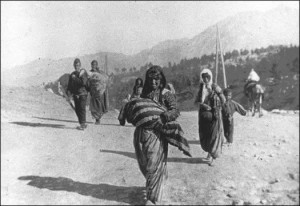

An expulsion of women and children.

The Peace Pledge Union provides a history of the hi-tech slaughter. ‘The genocide was conducted in a well-organised way, making use of new technology available’, the authors explain. Once the genocide had ‘officially’ started in 1915, ‘the perpetrators kept in touch by telegraph’, which, as we have seen, was pushed on Turkey by Britain. ‘They also made use of the Istanbul-Baghdad railway: the new line had already been laid as far as the Syrian desert. Tens of thousands of Armenians were packed into railway wagons and sent down the line into the desert, where they were left without shelter, water or food’—the railways paid for with German, French, and British bonds. ‘Many of the workers laying the railway were Armenian, and thought they would escape; their turn for the death trucks came in 1916’.12

All the talk of humanitarian intervention—used today in Serbia, Libya, and elsewhere to justify nakedly self-interested neo-imperial policies—came to nothing, a point of grievance for Turkish historian Taner Akcam, one of the few to recognise the genocide. Humanitarian intervention was a phrase used ‘to legitimize the most obvious colonial moves’. Germany mapped out plans for colonies. For Britain, ‘Ottoman land was simply an object of exploitation … Despite these intentions, the Great Powers presented their interventions in Ottoman affairs as humanitarian’.13

Beheaded Armenian men.

Reviewing the history, Akcam concludes that ‘[i]nterventions in the domestic affairs of nation-states are extremely problematic. In most cases, they produce results that are more detrimental than advantageous … As a rule, humanitarian goals mask imperialist policies and interests. Furthermore, in many cases, demands for intervention for humanitarian purposes are manipulated for internal political reasons’ . During the bombing of Serbia in 1999 under humanitarian pretexts, Turkey was killing thousands of Kurds—with British arms. No humanitarian concern was paid to the Kurds, to give one of innumerable examples.14

A row of Armenian skeletons.

Britain is, of course, unable to face its own responsibility for the genocide. Today, it is unwilling to push Turkey to recognise the genocide. A Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) file, obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, states: ‘given the importance of our relations (political, strategic and commercial) with Turkey … the current line is the only feasible option’. Historian Geoffrey Roberts notes that in 2014, ‘there was even talk at the FCO of giving to the Armenian Genocide Museum copies of some files in the National Archives attesting to the Ottoman atrocities: this was turned down, ostensibly because the photocopying costs of £431.20 could not be afforded, but probably because the Turks would go ballistic’.15

NOTES

1. Yakup Bektas, ‘The Sultan’s Messenger: Cultural Constructions of Ottoman Telegraphy, 1847-1880’, Technology and Culture, 41.4, 2000, pp. 669-696.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Yorulmaz, 2014, Arming the Sultan, IB Tauris.

5. ‘The Armenian Genocide and the British Response’, Head Heritage, 10 August, 2004, https://www.headheritage.co.uk/uknow/features/?id=55

6. Reverend Geography H. Hepworth, 1898, Through Armenia on Horseback, Ibister and Co., p. 157.

7. Ibid.

8. Rifleman.org, ‘Wilkinson sub-target machine’, no date, https://www.rifleman.org.uk/Wilkinson_sub-target_machine.htm and ‘BSA: early history’, no date, https://www.rifleman.org.uk/BSA_early_history.htm

9. On Britain’s investments, see Yorulmaz, op cit. Yakup Bektas, ‘Railways’, in Gábor Ágoston and Bruce Masters (eds.), Encyclopaedia of the Ottoman Empire, 2009, Facts On File, Inc. pp. 482-4.

10. Quoted in Robert Fisk, 2005, The Great War for Civilisation, HarperPerennial, p. 390.

11. Aneurin Williams, ‘Foreign Office (Class II)’, HC Debate 10 July, 2014, vol. 64 cc1383-463,

12. PPU, ‘Genocide: Armenia’, no date, https://www.ppu.org.uk/genocide/g_armenia1.html

13. Taner Akcam, 2007, A Shameful Act, Constable Robinson, pp. 424, 413, 76.

14. Ibid.

15. Geoffrey Robertson, ‘Armenians want acknowledgement that 1915 massacre was crime’, Guardian, 23 January, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/jan/23/armenians-want-acknowledgment-that-1915-massacre-was-crime-geoffrey-Robertson