Did Nuking Japan End World War II?

By T.J. Coles

22 June, 2015.

Before Pearl Harbor, Japan found it hard to forget that ‘The U.S. military actively engaged in planning with the British, the British Commonwealth countries, and the Dutch East Indies for future combined combat operations against Japan’, in the words of Dr. Robert Higgs, a Fellow at the Ludwig von Mises Institute. ‘Most important’, Higgs continued, ‘the U.S. government engaged in a series of increasingly stringent economic warfare measures that pushed the Japanese into a predicament that U.S. authorities well understood would probably provoke them to attack U.S. territories and forces in the Pacific region in a quest to secure essential raw materials that the Americans, British, and Dutch (government in exile) had embargoed’.

Higgs goes on to point out that Japan’s Foreign Minister Teijiro Toyoda communicated to Ambassador Kichisaburo Nomura that ‘Commercial and economic relations between Japan and third countries, led by England and the United States, are gradually becoming so horribly strained that we cannot endure it much longer. Consequently, our Empire, to save its very life, must take measures to secure the raw materials of the South Seas’.

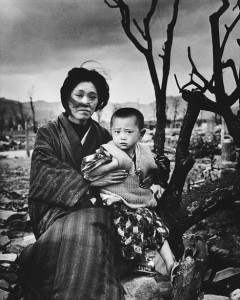

Historian Mark Weber asks if, militarily, the use of atomic bombs, and the instantaneous murder of 200,000 people was necessary. ‘By any rational yardstick, they were not’. Weber concludes that Japan had already ‘been defeated militarily by June 1945. Almost nothing was left of the once mighty Imperial Navy, and Japan’s air force had been all but totally destroyed. Against only token opposition, American war planes ranged at will over the country, and US bombers rained down devastation on her cities, steadily reducing them to rubble’.

The history is comparable to the recent history of Iraq, where, by the late-1990s, Saddam Hussein’s military had been significantly weakened by the Gulf War (1991), years of illegal ‘no-fly zone’ by the US and British aircraft, and of course the sanctions, which killed 1.5 million Iraqis. By the time Shock and Awe was unleashed on Baghdad with its ‘massive levels of destruction …[,] the non-nuclear equivalent’ of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, to quote the paper, Shock and Awe (1996), Iraq was easy to invade and clearly posed no threat to anyone.

Weber notes that on 20 January, 1945, ‘President Roosevelt received a 40-page memorandum from General Douglas MacArthur outlining five separate surrender overtures from high-level Japanese officials … In April and May 1945, Japan made three attempts through neutral Sweden and Portugal to bring the war to a peaceful end’. After the War, President Eisenhower conceded that ‘The Japanese were ready to surrender and it wasn’t necessary to hit them with that awful thing’, meaning the nuclear weapons.

Brigadier General Bonnie Fellers said: ‘Neither the atomic bombing nor the entry of the Soviet Union into the war forced Japan’s unconditional surrender. She was defeated before either these events took place’, echoing Admiral Leahy, Chief of Staff to Presidents Roosevelt and Truman: ‘the use of the barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan … The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons’ (Weber’s ellipsis). And on and on.

Nuclear war and/or accident is not inevitable, but as long as the British and American publics remain largely uninformed about America’s commitment to Full Spectrum Dominance, such terminal catastrophes grow increasingly likely.

SOURCES

Jonathan Glover, 1991, Humanity: A Moral History of the Twentieth Century, Pimlico.

Robert Higgs, ‘How U.S. Economic Warfare Provoked Japan’s Attack on Pearl Harbor’, 7 December, 2012, Mises Institute, https://mises.org/library/how-us-economic-warfare-provoked-japans-attack-pearl-harbor

Mark Weber, ‘Was Hiroshima Necessary? Why the Atomic Bombings Could Have Been Avoided’, The Journal of Historical Review, May-June 1997, Vol. 16, No. 3, pages 4-11.