Magna Carta Not So Magna: Why Celebrate “Rights” Imposed By Elites?

By T.J. Coles

24 June, 2015

The octocentenary of Magna Carta is celebrated by the establishment this June, and with good reason. There were several editions of Magna Carta but the famous first edition of 1215, repealed a year later, codified certain rights for the ruling classes, especially the Catholic Church in England, which ‘shall be free, and shall have its rights undiminished, and its liberties unimpaired’ (Article 1).

A doctrine that dominant minorities have a moral right—even responsibility—to impose law, even laws that in some ways help their subjects, is an internalised convention. So much so, that the octocentenary elicited much patriotic self-admiration. Democratic Audit’s Andrew Blick calls Magna Carta ‘a surprisingly enduring document which still influences our political and democratic choices to this day’ (Blick 2015).

Others (see below) were more acerbic, but their criticism was that the British government were failing to meet the standards enshrined in Magna Carta. By definition, though, their position was the same: they admire a document imposed by the few, rather than condemn it for being codified outside democratic control. Before (and to some degree during) the Norman Conquest, England was a land of petty monarchs and loose tribes, the latter with their own oral laws and moral codes. To praise Magna Carta is to praise the brutal nation-state system, the foundations of which were laid by the Catholic Church.

There is no reason why the moral codes of less hierarchical tribes cannot be revived and celebrated.

BACKGROUND

Since the Norman Conquest, England’s feudal system had been of immense benefit to the landowning class of barons and knights. John came to power in 1199, shortly after Richard I died of gangrene. England was at war with France’s King Philip Augustus and drained by famine. John outraged elite opinion with his marital habits and by capturing and murdering his nephew in secret. Pope Innocent III installed Stephen Langton as Archbishop of Canterbury. John refused to recognise Langton and was excommunicated by Innocent, who essentially put England under sanctions, closing its Catholic churches (Strong 1998).

Magna Carta was a way of putting a rebel king under control.

The baronage was a system enforced by violence. Often, the more knights willing to follow the given king or baron, the more successful the elite. By the time John came to power, ‘Mercenary crossbowmen were fully as effective as knights, and knights could be hired and equipped for money’. Perhaps for the first time in English history, ‘Money had become the source of power. Unfortunately, John found himself at a serious disadvantage under a money [system]’, writes historian Sidney Painter (1947).

Historian Walter Ullman writes: ‘it was the tyranny of John which had turned the baronial right of joining in legislation into a reality’ (Ullman 1968). Langton met with the barons at St. Albans in 1214 to show them the Charter of Liberties, sealed under the reign of Henry I. The Charter of Liberties ‘served as the model for the Great Charter’ (Fordham Un. undated) and revealed to the barons that John was in violation of Henry I’s pledges. Ergo, Magna Carta was not England’s first ‘human rights’ document.

Archbishop Langton.

ELITE RIGHTS BEFORE 1215

Magna Carta is praised by historians and commentators for codifying evidence-based trials by a jury of peers. However, the article a) applied to ‘freemen’, putting the majority of England’s serf and slave populations to disadvantage and b) was not original. ‘[T]he first recorded appearance of habeas corpus was, in fact, in 1199, predating the Magna Carta by 16 years’, writes historian Justin J. Wert. ‘Originally part of the mesne process of early legal adjudication, the writ was widely used to ensure the presence of parties in court’ (Wert 2010).

Marking Magna Carta’s 700th anniversary, Columbia Law Review published a paper pointing out that Magna Carta was ‘a concession to the demands of the barons for a return to the feudal anarchy of Stephen’s time and a repeal of the great administrative measures by which Henry II and his predecessors were molding a national judicial system, and thus preparing the way for a common law’. Magna Carta was in fact the codification of barons ‘trying their own feudal dependents in their own courts by the customs of their own fiefs’ (C.H. McIlwain 1914).

Article 9, for instance, states: ‘If they so desire, they may have the debtor’s lands and rents until they have received satisfaction for the debt that they paid for him, unless the debtor can show that he has settled his obligations to them’.

Magna Carta’s class-based limitations and misogyny are judged today by the standards and mores of the time. Painter points out that ‘this concept is not essentially democratic and’—significantly—‘had no slightest democratic element in the time of Magna Carta’. It was and was intended to be a document appeasing the upper-classes. No sooner had John sealed Magna Carta, he ‘promptly called for Poitevin and Gascon troops and dispatched messengers to Rome to persuade the pope to declare the charter invalid’.

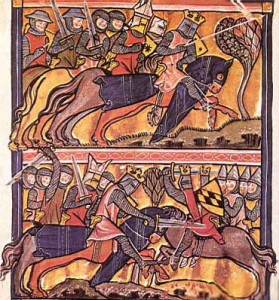

King John’s failure to live up to Magna Carta led to England’s ‘first civil war’, the First Barons’ War of 1215.

First Barons’ War.

MAGNA CARTA TODAY

So effective is Magna Carta that 800 years on Justice Alliance-co-founder and solicitor Matt Foot told the Guardian that, ‘At a time when the government have decimated legal aid because they say we cannot afford it, it’s great they have found the money to put on a massive business-fest in celebration of free enterprise and Magna Carta’, referring to the three-day, £1,750-a ticket Global Law Summit. Liberty’s director, Shami Chakrabarti, boycotted the Summit, saying: ‘This event has been promoted by a government which has decimated access to justice’ (Bowcott 2015).

The New Statesman reports that the Tory-Liberal regime’s LASPO Act 2013 ‘removed legal aid for the majority of cases – with some specific exceptions – involving divorce, welfare benefits, clinical negligence and child contact’. The article concludes that ‘Some of the groups worst affected – young people in care, the homeless, migrants – are also society’s most voiceless’ (Shackle 2014).

The Law Society notes that ‘in the past decade, the European Court of Human Rights has made 19 rulings against the UK and 1,237 rulings against all EU countries in total for breaches to the right to a fair trial’ (Cross 2015).

Abroad, thousands are murdered—with UK government support—in the CIA’s and US military’s drone programmes. Constitutional lawyer Stephen Rhodes writes: ‘everything that Magna Carta has come to symbolize has been severely tested in the War on Terror, as the United States government … has resorted to torture, indefinite detentions, and extrajudicial targeted assassinations by killer drones’ (Rhodes 2015).

One place in which ‘war on terror’ victims are renditioned (i.e., kidnapped and tortured) is Diego Garcia, islands from which the British government forcibly expelled the civilian population in the 1960s and 1970s so that the US could build a military base. Despite the High Court judge’s invocation of Magna Carta, the people still haven’t the right to return, partly because Elizabeth II invoked her Royal Prerogative to prevent the islanders from returning, and also because of the brute force of US security around the islands (Pilger 2006).

These and innumerable examples demonstrate that Magna Carta is a thing to mourn, not celebrate. We can perhaps celebrate when communities make their own laws representing the interests and concerns of everyone in that community.

SOURCES

Andrew Blick, ‘Magna Carta can still challenge the orthodox and help resolve today’s democratic difficulties’, London School of Economics, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/magna-carta-can-still-challenge-the-orthodoxy-and-help-resolve-todays-democratic-difficulties/

Owen Bowcott, ‘Justice campaigners propose boycott of Magna Carta anniversary summit’, Guardian, 1 February, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/law/2015/feb/01/global-law-summit-magna-carta-boycott

Michael Cross, ‘Magna Carta ‘still essential today’’, Law Society Gazette, 15 June, 2015, https://www.lawgazette.co.uk/news/magna-carta-still-essential-today/5049380.fullarticle

Fordham University, ‘Medieval Sourcebook: Charter of Liberties of Henry I, 1100’ no date, https://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/source/hcoronation.asp

H. McIlwain, ‘Due Process of Law in Magna Carta’, Columbia Law Review, Vol. 14, No. 1, January, 1914, pp. 27-51.

Sidney Painter, ‘Magna Carta’, The American Historical Review, Vol. 53, No. 1, October, 1947, pp. 42-49.

John Pilger, 2006, Freedom Next Time, Black Swan.

Stephen Rhodes, ‘Magna Carta and the Rule of Law’, LA Review of Books, 14 June, 2015, https://lareviewofbooks.org/review/magna-carta-from-discontented-barons-to-predator-drones

Samira Shackle, ‘How legal aid cuts are harming the voiceless and most vulnerable’, New Statesman, 13 January, 2014, https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/2014/01/how-legal-aid-cuts-are-harming-voiceless-and-most-vulnerable

Walter Ullman, 1968, A History of Political Thought: The Middle Ages, Penguin.

Justin J. Wert, ‘With a Little Help from a Friend: Habeas Corpus and the Magna Carta after Runnymede’, Political Science and Politics, Vol., 43, No. 3, July 2010, pp. 475-478.